Table of Contents

Winter 2015

Welcome to the Winter 2015 issue! Actually, by the time you receive this, Winter should be in the final days across the state, and Spring on the horizon. This issue marks the first to be integrated within to our new website! Continue to see additions and content as we continue through the year, leading up to Conference 2015 in Harrisburg!

Jonathan DeBor

Communications Director

pctelanews@gmail.com

Jonathan DeBor

Communications Director

pctelanews@gmail.com

PCTELA Conference 2015 - Featured Speaker

We are pleased to announce one of our featured speakers for CONFERENCE 2015…

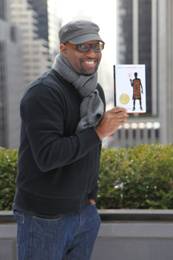

Newbery Award Winning Author, Kwame Alexander

Kwame Alexander is a poet and author of eighteen books, including The Crossover, which received the 2015 John Newbery Medal for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children. Other works include Acoustic Rooster and His Barnyard Band (The 2014 Michigan Reads One Book Selection), and the YA novel He Said, She Said (a Junior Library Guild Selection). He is the founder of Book-in-a-Day, a student-run publishing program that has created more than 3000 student authors; and LEAP for Ghana, an international literacy project that builds libraries, trains teachers, and empowers children through literature. He visits schools and libraries, has owned several publishing companies, written for stage and television, produced jazz and book festivals, and taught in a high school. In 2015, Kwame will serve as Bank Street College of Education’s first writer-in-residence. Visit him at www.kwamealexander.com.

Kwame Alexander will speak on Saturday of Conference 2015

Newbery Award Winning Author, Kwame Alexander

Kwame Alexander is a poet and author of eighteen books, including The Crossover, which received the 2015 John Newbery Medal for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children. Other works include Acoustic Rooster and His Barnyard Band (The 2014 Michigan Reads One Book Selection), and the YA novel He Said, She Said (a Junior Library Guild Selection). He is the founder of Book-in-a-Day, a student-run publishing program that has created more than 3000 student authors; and LEAP for Ghana, an international literacy project that builds libraries, trains teachers, and empowers children through literature. He visits schools and libraries, has owned several publishing companies, written for stage and television, produced jazz and book festivals, and taught in a high school. In 2015, Kwame will serve as Bank Street College of Education’s first writer-in-residence. Visit him at www.kwamealexander.com.

Kwame Alexander will speak on Saturday of Conference 2015

CONFERENCE 2015: - EMBRACING DIVERSITY

October 16 & 17, 2015

Harrisburg Hilton

Harrisburg, PA

October 16 & 17, 2015

Harrisburg Hilton

Harrisburg, PA

Conference Reflection

Anne Schober

2014 PCTELA Conference Chairperson

Chaos. Panic. Excitement. Chaos. Panic. Excitement. Those three emotions became immersed in my daily life over the course of a year in planning the 2014 PCTELA conference. But, in the end, it was all worth it! From the friendships formed, the smiles witnessed and the connections made, the energy and enthusiasm from all involved helped to transform my feelings of chaos and panic into peace and fulfillment. “Energized Teachers + Engaged Students = SUCCESS!” was a weekend that far exceeded my expectations and it is all because of the participants, presenters, keynote speakers, and the PCTELA board… words can never express my utmost gratitude and respect for all involved.

When asked to reflect on the conference, I knew that I would be able to fill this entire newsletter with tidbits and musings, so I decided to “borrow” the Top Ten List format from David Letterman to better capture my thoughts in a more concise manner.

The Top 10 Reasons Why the 2014 PCTELA Conference was Successful:

10. The Double Tree Hilton. What a great venue! From the beautiful guest rooms, ballrooms, delicious food and the great staff, the whole event ran like clockwork! A perfect location for a great weekend!

9. The Vendors. No conference would be complete without the help and sponsorship's of the vendors who come each year to share their goods and talents with those in attendance. Hats off to all of you!

8, 7, 6, and 5. Keynote Speakers. Kicking off a conference holds a lot of responsibility and Thom Stecher accepted the challenge and rose to the occasion! From tears to laughter, each participant left the opening presentation realizing the importance of their profession and felt reignited with passion and hope! Stephen Chbosky, the talent behind The Perks of Being a Wallflower, ended the first day of the conference discussing the writing of his book, how he discovered the main character(s), and how his book has connected with students. In fact, a small group of students from Penn Trafford High School was given a special session with the person they consider “their hero” on Friday afternoon, and the impact Stephen made on them was profoundly powerful. Beginning the second day of the conference can always be a little tough but ReLeah Lent hit it out of the park! She had the participants laughing, conversing, and reflecting and she kicked off the second day of the conference with gusto and enthusiasm! The conference ended with the musings and tales of Jay Asher, renowned author of Thirteen Reasons Why. Jay allowed for questions from the participants as well as sharing some stories behind his writing and the adventures he has encountered throughout his writing career. All four of the keynote speakers were engaging, enlightening and powerful and left each of the participants feeling rejuvenated and blessed.

4. Authors Breakfast. Saturday morning allowed the participants to have a breakfast with authors and each was given the chance to discuss the art of writing in a more personal atmosphere. This year included authors from all different genres sharing their books and talents with a packed house of engaged educators.

3. Breakout and Roundtable Sessions. On Friday and Saturday, outstanding educators from throughout Pennsylvania, shared their insights into the current best practices of the profession and offered some practical strategies for classroom activities. The Pennsylvania Writing Project Network offered a strand of educational opportunities for the participants, as well, and together each presentation proved to be valuable and insightful and helped to make the conference a successful adventure.

2. PCTELA Board. This Board is a group filled with some of the hardest working individuals I have ever had the honor to know. They embody the word “TEAM” and the 2014 conference was made successful because of their passion, energy and willingness to help and guide. The work for a conference begins the day the previous conference ends, and this group of AMAZING individuals never left my side through it all. They were my rock… words can never thank them enough for all they did!

And, the #1 reason why the 2014 PCTELA conference was a success is...

1. Participants. No conference would be complete without the participants. It was exciting to see the first participant sign in on Friday morning and then to hear the words of thanks and praise as they each left on Saturday afternoon. Because of each of you, the 2014 PCTELA conference was a success!

I was honored to be the chairperson and work with some of the finest people and educators I have ever had the pleasure of knowing; words cannot express my immense gratitude. Every person, every moment, every word spoken helped to make the weekend a beautiful memory. As in the words of Jay Asher, “In the end....everything matters.” Thank you for everything!

2014 PCTELA Conference Chairperson

Chaos. Panic. Excitement. Chaos. Panic. Excitement. Those three emotions became immersed in my daily life over the course of a year in planning the 2014 PCTELA conference. But, in the end, it was all worth it! From the friendships formed, the smiles witnessed and the connections made, the energy and enthusiasm from all involved helped to transform my feelings of chaos and panic into peace and fulfillment. “Energized Teachers + Engaged Students = SUCCESS!” was a weekend that far exceeded my expectations and it is all because of the participants, presenters, keynote speakers, and the PCTELA board… words can never express my utmost gratitude and respect for all involved.

When asked to reflect on the conference, I knew that I would be able to fill this entire newsletter with tidbits and musings, so I decided to “borrow” the Top Ten List format from David Letterman to better capture my thoughts in a more concise manner.

The Top 10 Reasons Why the 2014 PCTELA Conference was Successful:

10. The Double Tree Hilton. What a great venue! From the beautiful guest rooms, ballrooms, delicious food and the great staff, the whole event ran like clockwork! A perfect location for a great weekend!

9. The Vendors. No conference would be complete without the help and sponsorship's of the vendors who come each year to share their goods and talents with those in attendance. Hats off to all of you!

8, 7, 6, and 5. Keynote Speakers. Kicking off a conference holds a lot of responsibility and Thom Stecher accepted the challenge and rose to the occasion! From tears to laughter, each participant left the opening presentation realizing the importance of their profession and felt reignited with passion and hope! Stephen Chbosky, the talent behind The Perks of Being a Wallflower, ended the first day of the conference discussing the writing of his book, how he discovered the main character(s), and how his book has connected with students. In fact, a small group of students from Penn Trafford High School was given a special session with the person they consider “their hero” on Friday afternoon, and the impact Stephen made on them was profoundly powerful. Beginning the second day of the conference can always be a little tough but ReLeah Lent hit it out of the park! She had the participants laughing, conversing, and reflecting and she kicked off the second day of the conference with gusto and enthusiasm! The conference ended with the musings and tales of Jay Asher, renowned author of Thirteen Reasons Why. Jay allowed for questions from the participants as well as sharing some stories behind his writing and the adventures he has encountered throughout his writing career. All four of the keynote speakers were engaging, enlightening and powerful and left each of the participants feeling rejuvenated and blessed.

4. Authors Breakfast. Saturday morning allowed the participants to have a breakfast with authors and each was given the chance to discuss the art of writing in a more personal atmosphere. This year included authors from all different genres sharing their books and talents with a packed house of engaged educators.

3. Breakout and Roundtable Sessions. On Friday and Saturday, outstanding educators from throughout Pennsylvania, shared their insights into the current best practices of the profession and offered some practical strategies for classroom activities. The Pennsylvania Writing Project Network offered a strand of educational opportunities for the participants, as well, and together each presentation proved to be valuable and insightful and helped to make the conference a successful adventure.

2. PCTELA Board. This Board is a group filled with some of the hardest working individuals I have ever had the honor to know. They embody the word “TEAM” and the 2014 conference was made successful because of their passion, energy and willingness to help and guide. The work for a conference begins the day the previous conference ends, and this group of AMAZING individuals never left my side through it all. They were my rock… words can never thank them enough for all they did!

And, the #1 reason why the 2014 PCTELA conference was a success is...

1. Participants. No conference would be complete without the participants. It was exciting to see the first participant sign in on Friday morning and then to hear the words of thanks and praise as they each left on Saturday afternoon. Because of each of you, the 2014 PCTELA conference was a success!

I was honored to be the chairperson and work with some of the finest people and educators I have ever had the pleasure of knowing; words cannot express my immense gratitude. Every person, every moment, every word spoken helped to make the weekend a beautiful memory. As in the words of Jay Asher, “In the end....everything matters.” Thank you for everything!

How Students Become Change Agents: Using the Teach-In to Address Campus Issues

Teresa A. Narey

Adjunct Instructor

English Department

Robert Morris University

The semester has just started and I’m already planning my final exam. I teach Argument and Research, a first-year writing class at Robert Morris University. Over the course of the semester, my students choose one topic to examine in their three major papers—an exploratory essay, research paper, and persuasive essay—with the hope that they will start to understand that research is a process and writing well-intentioned arguments requires a lot of supporting research.

In my class, students often learn for the first time that not all arguments have resolutions. In fact, one of the first lessons they learn is that when it comes to moral issues, things like abortion, the death penalty, and euthanasia, our arguments are so entangled with our beliefs and worldviews that it’s hard to arrive at a solution that will appear reasonable to everyone. The essence of argument is compromise. It takes a lot of strategy on my part to help my students grasp this.

At the end of the semester when my students turn in their persuasive essays, some have arrived at compromise. Still, others struggle to see beyond their own perspectives. It’s hard to gauge who feels accomplished because all of them are burned out and eager for vacation. This semester I want them to see how their arguments exist in the real world, how beyond meeting course objectives, they can become change agents.

“Change agent” is a term that is becoming ever more salient as the Maker Movement continues to inspire many in the education community and the demand for innovation drives new efforts in workforce development. Robert Morris boasts a 92% placement rate. Many of my students are majoring in engineering, actuarial science, nursing, and hospitality management. Such professions require workers to think creatively, strategically, and globally. Being able to lead and problem solve on the spot will be essential for my students. Thus, my class, which encourages sound decision making and critical thinking, should be a top priority, but they just see it as another writing class—a requirement to get out of the way so they can get on with their majors.

With this in mind, I’ve decided to design my final as a teach-in, a meeting where students will inform their peers about a campus issue and offer a plan of action for taking on that issue. For their major papers, many of my students want to examine big questions, like gun control, health care, and fracking—issues they don’t know much about, save that these questions have an impact on their communities. Questions such as these are difficult for political leaders to resolve, let alone the 18-year-olds sitting in my classroom. While it is important for my students to familiarize themselves with the dilemmas of modern society, they will continue to feel powerless unless they have some experience solving smaller, more meaningful challenges.

For the teach-in, my students will work in groups to find a practical solution to a campus issue. Their task will be to produce a distributable body of work; that is, they will make a brochure, PSA, commercial, flyer, etc., that will help spread the word about how their peers can help in solving a particular campus problem, or at least supporting an act of compromise. Beyond the desire to give my students an action-oriented task, the teach-in crept into my mind after reflecting on my students’ work from last semester.

In the fall, one of my students wrote about the problem of college students not getting enough sleep. Through research, he learned that only a handful of universities make an effort to educate their students about good sleep habits. According to the student, Robert Morris doesn’t address sleep habits to any great extent, but he recognized that the university’s mandatory First-Year Seminar Program would be a good venue for addressing this concern with students. His peers heard this idea when he gave an oral presentation, but the idea fell flat once the semester ended. It occurred to me that if we had organized a teach-in, he could have made a PSA or designed a workshop to take on this issue. His work could have had an impact across the campus instead of just in class. His idea might have been catching. Next fall, incoming first-years may have been educated about sleep habits. He could have been a change agent.

My goal as a teacher is to encourage my students to be proactive, but more importantly, I want them to develop the confidence and social awareness to care about being proactive. We tend to think of writing and research as stationary experiences. We imagine the student hunkered down in the library, googling search terms or sifting through books, collecting and assembling bits of information to get the paper done on time. Teachers of writing know that the process is so much more. We know that writing can inform, and when writing is connected to community, change is possible.

Adjunct Instructor

English Department

Robert Morris University

The semester has just started and I’m already planning my final exam. I teach Argument and Research, a first-year writing class at Robert Morris University. Over the course of the semester, my students choose one topic to examine in their three major papers—an exploratory essay, research paper, and persuasive essay—with the hope that they will start to understand that research is a process and writing well-intentioned arguments requires a lot of supporting research.

In my class, students often learn for the first time that not all arguments have resolutions. In fact, one of the first lessons they learn is that when it comes to moral issues, things like abortion, the death penalty, and euthanasia, our arguments are so entangled with our beliefs and worldviews that it’s hard to arrive at a solution that will appear reasonable to everyone. The essence of argument is compromise. It takes a lot of strategy on my part to help my students grasp this.

At the end of the semester when my students turn in their persuasive essays, some have arrived at compromise. Still, others struggle to see beyond their own perspectives. It’s hard to gauge who feels accomplished because all of them are burned out and eager for vacation. This semester I want them to see how their arguments exist in the real world, how beyond meeting course objectives, they can become change agents.

“Change agent” is a term that is becoming ever more salient as the Maker Movement continues to inspire many in the education community and the demand for innovation drives new efforts in workforce development. Robert Morris boasts a 92% placement rate. Many of my students are majoring in engineering, actuarial science, nursing, and hospitality management. Such professions require workers to think creatively, strategically, and globally. Being able to lead and problem solve on the spot will be essential for my students. Thus, my class, which encourages sound decision making and critical thinking, should be a top priority, but they just see it as another writing class—a requirement to get out of the way so they can get on with their majors.

With this in mind, I’ve decided to design my final as a teach-in, a meeting where students will inform their peers about a campus issue and offer a plan of action for taking on that issue. For their major papers, many of my students want to examine big questions, like gun control, health care, and fracking—issues they don’t know much about, save that these questions have an impact on their communities. Questions such as these are difficult for political leaders to resolve, let alone the 18-year-olds sitting in my classroom. While it is important for my students to familiarize themselves with the dilemmas of modern society, they will continue to feel powerless unless they have some experience solving smaller, more meaningful challenges.

For the teach-in, my students will work in groups to find a practical solution to a campus issue. Their task will be to produce a distributable body of work; that is, they will make a brochure, PSA, commercial, flyer, etc., that will help spread the word about how their peers can help in solving a particular campus problem, or at least supporting an act of compromise. Beyond the desire to give my students an action-oriented task, the teach-in crept into my mind after reflecting on my students’ work from last semester.

In the fall, one of my students wrote about the problem of college students not getting enough sleep. Through research, he learned that only a handful of universities make an effort to educate their students about good sleep habits. According to the student, Robert Morris doesn’t address sleep habits to any great extent, but he recognized that the university’s mandatory First-Year Seminar Program would be a good venue for addressing this concern with students. His peers heard this idea when he gave an oral presentation, but the idea fell flat once the semester ended. It occurred to me that if we had organized a teach-in, he could have made a PSA or designed a workshop to take on this issue. His work could have had an impact across the campus instead of just in class. His idea might have been catching. Next fall, incoming first-years may have been educated about sleep habits. He could have been a change agent.

My goal as a teacher is to encourage my students to be proactive, but more importantly, I want them to develop the confidence and social awareness to care about being proactive. We tend to think of writing and research as stationary experiences. We imagine the student hunkered down in the library, googling search terms or sifting through books, collecting and assembling bits of information to get the paper done on time. Teachers of writing know that the process is so much more. We know that writing can inform, and when writing is connected to community, change is possible.

Thoughts on Writing Book Reviews

Thomas Hansen

Somebody asked me lately about my writing and whether I was into stories or poetry. I answered, “Mostly, I write book reviews for teachers.” Having taught various subjects, I can see uses for texts and correlations across fields.

I have also written a few movie reviews, a couple poems, some stories and articles, and a couple dozen essays. Some of my work has been published right away…but not every piece has been that popular. I have some pieces that have never been published. Some of them have remained in folders for a couple decades, actually. Some of those pieces will never be read.

So who reads my writing? By far, my highest readership is from teachers seeing my reviews in journals, newsletters, workshop handouts, and now: online communications. Most of my favorite writing remains in the world of book reviews for teachers, also. It is exciting when I am at a statewide conference and teachers mention they have read one of my reviews!

One of my favorite sorts of book reviews has to do with developing curriculum or methods ideas from a text in one field for a classroom focused on a different—often very different—field. There is so much teachers can learn from each other; communication is key.

I look at chapters for content, quotations, and examples of discipline-specific information I can draw on. I try to imagine what teachers of various fields would do if they had to teach the particular material. I try to think about how they would teach it—and test it.

Another interesting approach is to read a book on current issues or popular topics and write reviews of the book for teachers. There are a lot of essential books for teachers to read. Since all teachers change society, they should read: The lifelong activist, by Hillary Rettig. Another book teachers should be reading right now is Someplace like America, by Maharidge and Williamson—because a knowledge of the current Great Depression is essential for teachers. A third important book is The border crossed us, by Cisneros. Knowing about borders and citizenship in context makes us more informed as we develop political opinions.

Still other important books can be used to develop curriculum and lesson. For example, a book on the history of the automobile is good background reading for social studies teachers. Some students very interested in cars may get more involved in their social studies or history classes if they come to understand what happened to auto factories before, during, and after World War II. I maintain The life of the automobile would be very helpful in reaching certain students. The teacher could write lesson plans, assign homework, ask students to look for Internet links, and hold discussions on concepts and issues like: nationalizing property; Hitler’s war machine; US investment abroad leading up to the era of World War II; and the roles of French, Italian, and British governments in the production of autos. Teachers can include visually-oriented learners by looking into the shape and design of autos. They can include technically-focused students on how engines work, what fuels are needed, what happens with the exhaust. Further, they can include aural and visual learners by looking at videos of car production in the past. Musical learners will perhaps be interested in jingles about new auto models that appeared each year in the past… such as in the 1960s… car models differed radically each year in the past—not like now when cars from one year look almost identical to the car models of the following year. These are a few examples of a teacher using a popular book to come up with ideas for helping students make connections and get more from their classes.

Of course, students need to read all the time—and for all of their classes. Teachers of English, language arts, world languages, and reading must digest a huge amount of information also. Teachers of ESL and bilingual education too! Making lots of different materials available to students is essential, so teachers must keep reviewing books to see what can be helpful. It is so important to make assignments, projects, and exams relevant. Having an arsenal of ammunition handy keeps teachers prepared in the battle of keeping those students reading!

Unfortunately, getting students to commit to our units and lessons is sometimes like a game. Getting students to learn something is one of our main goals as teachers—but it somedays can seem so difficult. I think that some of the best teachers I have known have been very interdisciplinary individuals. They lived lives full of a very wide range of interests and activities. Some were true experts on raising children. Others were experts on football, others on baseball or cooking or wine or dogs. Still others were great at playing golf or basketball or scrabble. Some made crafts, designed their own holiday greeting cards, led book clubs, and belonged to support groups. Some taught weird combinations of courses, taught English, coached softball, and volunteered in food pantries.

It is the memory of such great teachers—and their always hard-working students—that drive some of my book reviews. What can teachers learn from other teachers? A great deal, I believe. It is our private club. Non-teachers don’t know about our secret handshakes or about our multi-faceted personalities!

References:

-Cisneros, J. (2014). The border crossed us: Rhetorics of borders, citizenship, and Latina/o identity. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

-Maharidge, D., & Williamson, M. (2013). Someplace like America: Tales from the New Great Depression. Berkeley: University of California Press.

-Parissien, S. (2014). The life of the automobile: The complete history of the motor car. London: Thomas Dunne Books.

-Rettig, H. (2006). The lifelong activist: How to change the world without losing your way. New York: Lantern Books.

Somebody asked me lately about my writing and whether I was into stories or poetry. I answered, “Mostly, I write book reviews for teachers.” Having taught various subjects, I can see uses for texts and correlations across fields.

I have also written a few movie reviews, a couple poems, some stories and articles, and a couple dozen essays. Some of my work has been published right away…but not every piece has been that popular. I have some pieces that have never been published. Some of them have remained in folders for a couple decades, actually. Some of those pieces will never be read.

So who reads my writing? By far, my highest readership is from teachers seeing my reviews in journals, newsletters, workshop handouts, and now: online communications. Most of my favorite writing remains in the world of book reviews for teachers, also. It is exciting when I am at a statewide conference and teachers mention they have read one of my reviews!

One of my favorite sorts of book reviews has to do with developing curriculum or methods ideas from a text in one field for a classroom focused on a different—often very different—field. There is so much teachers can learn from each other; communication is key.

I look at chapters for content, quotations, and examples of discipline-specific information I can draw on. I try to imagine what teachers of various fields would do if they had to teach the particular material. I try to think about how they would teach it—and test it.

Another interesting approach is to read a book on current issues or popular topics and write reviews of the book for teachers. There are a lot of essential books for teachers to read. Since all teachers change society, they should read: The lifelong activist, by Hillary Rettig. Another book teachers should be reading right now is Someplace like America, by Maharidge and Williamson—because a knowledge of the current Great Depression is essential for teachers. A third important book is The border crossed us, by Cisneros. Knowing about borders and citizenship in context makes us more informed as we develop political opinions.

Still other important books can be used to develop curriculum and lesson. For example, a book on the history of the automobile is good background reading for social studies teachers. Some students very interested in cars may get more involved in their social studies or history classes if they come to understand what happened to auto factories before, during, and after World War II. I maintain The life of the automobile would be very helpful in reaching certain students. The teacher could write lesson plans, assign homework, ask students to look for Internet links, and hold discussions on concepts and issues like: nationalizing property; Hitler’s war machine; US investment abroad leading up to the era of World War II; and the roles of French, Italian, and British governments in the production of autos. Teachers can include visually-oriented learners by looking into the shape and design of autos. They can include technically-focused students on how engines work, what fuels are needed, what happens with the exhaust. Further, they can include aural and visual learners by looking at videos of car production in the past. Musical learners will perhaps be interested in jingles about new auto models that appeared each year in the past… such as in the 1960s… car models differed radically each year in the past—not like now when cars from one year look almost identical to the car models of the following year. These are a few examples of a teacher using a popular book to come up with ideas for helping students make connections and get more from their classes.

Of course, students need to read all the time—and for all of their classes. Teachers of English, language arts, world languages, and reading must digest a huge amount of information also. Teachers of ESL and bilingual education too! Making lots of different materials available to students is essential, so teachers must keep reviewing books to see what can be helpful. It is so important to make assignments, projects, and exams relevant. Having an arsenal of ammunition handy keeps teachers prepared in the battle of keeping those students reading!

Unfortunately, getting students to commit to our units and lessons is sometimes like a game. Getting students to learn something is one of our main goals as teachers—but it somedays can seem so difficult. I think that some of the best teachers I have known have been very interdisciplinary individuals. They lived lives full of a very wide range of interests and activities. Some were true experts on raising children. Others were experts on football, others on baseball or cooking or wine or dogs. Still others were great at playing golf or basketball or scrabble. Some made crafts, designed their own holiday greeting cards, led book clubs, and belonged to support groups. Some taught weird combinations of courses, taught English, coached softball, and volunteered in food pantries.

It is the memory of such great teachers—and their always hard-working students—that drive some of my book reviews. What can teachers learn from other teachers? A great deal, I believe. It is our private club. Non-teachers don’t know about our secret handshakes or about our multi-faceted personalities!

References:

-Cisneros, J. (2014). The border crossed us: Rhetorics of borders, citizenship, and Latina/o identity. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

-Maharidge, D., & Williamson, M. (2013). Someplace like America: Tales from the New Great Depression. Berkeley: University of California Press.

-Parissien, S. (2014). The life of the automobile: The complete history of the motor car. London: Thomas Dunne Books.

-Rettig, H. (2006). The lifelong activist: How to change the world without losing your way. New York: Lantern Books.

Not My Own Words

Bob Hamera

John E. Usalis is a journalist for our local newspaper, The Pottsville Republican Herald. Each Sunday he writes a column that he calls “Wanderings”. On a recent Sunday I really enjoyed his column so I thought I would share some of his words of wisdom. The majority of this article belongs to him and not me.

John devoted his Sunday column to rules for writing. He credits Frank L. Visco for coming up with the first 11 and the rest he got from other sources. I’m including all 22 because I think they are worthwhile. Here goes…just the way it appeared in Sunday’s paper. I got a chuckle out of them and I hope you do as well.

1. Avoid alliteration. Always.

2. Prepositions are not words to end sentences with.

3. Avoid clichés like the plague. They’re old hat.

4. Eschew ampersands & abbreviations, etc.

5. Writers should never generalize.

6. Comparisons are as bad as clichés.

Seven. Be consistent.

8. Be more or less specific.

9. Sentence fragments. Eliminate.

10. Exaggeration is a billion times worse than understatement.

11. Parenthetical remarks (however relevant) are unnecessary.

12. Who needs rhetorical questions?

13. Never write one word sentences. Period.

14. Never use mixed metaphors. That is like comparing apples to a picture worth a thousand oranges.

15. Above all else, be terse. Don’t carry on and on and on. No one likes to keep reading and reading and reading and reading and not go anywhere with it. Make sure that your reader understands what you are trying to convey in as few words as possible, and that you really are trying to limit your words however you can.

16. Don’t use no double negatives.

17. Don’t repeat yourself.

18. About them sentence fragments.

19. Quit putting commas, where they don’t belong.

20. Don’t repeat yourself.

21. always start a sentence with a capitol letter and end with punctuation

22. Proofread you writing.

As a former English teacher I really got a kick out of reading this column. Even though I did not write it, I just had to share. Hope you enjoyed. I’ll keep on the lookout for future words of wisdom from him that I can share at a later date.

John E. Usalis is a journalist for our local newspaper, The Pottsville Republican Herald. Each Sunday he writes a column that he calls “Wanderings”. On a recent Sunday I really enjoyed his column so I thought I would share some of his words of wisdom. The majority of this article belongs to him and not me.

John devoted his Sunday column to rules for writing. He credits Frank L. Visco for coming up with the first 11 and the rest he got from other sources. I’m including all 22 because I think they are worthwhile. Here goes…just the way it appeared in Sunday’s paper. I got a chuckle out of them and I hope you do as well.

1. Avoid alliteration. Always.

2. Prepositions are not words to end sentences with.

3. Avoid clichés like the plague. They’re old hat.

4. Eschew ampersands & abbreviations, etc.

5. Writers should never generalize.

6. Comparisons are as bad as clichés.

Seven. Be consistent.

8. Be more or less specific.

9. Sentence fragments. Eliminate.

10. Exaggeration is a billion times worse than understatement.

11. Parenthetical remarks (however relevant) are unnecessary.

12. Who needs rhetorical questions?

13. Never write one word sentences. Period.

14. Never use mixed metaphors. That is like comparing apples to a picture worth a thousand oranges.

15. Above all else, be terse. Don’t carry on and on and on. No one likes to keep reading and reading and reading and reading and not go anywhere with it. Make sure that your reader understands what you are trying to convey in as few words as possible, and that you really are trying to limit your words however you can.

16. Don’t use no double negatives.

17. Don’t repeat yourself.

18. About them sentence fragments.

19. Quit putting commas, where they don’t belong.

20. Don’t repeat yourself.

21. always start a sentence with a capitol letter and end with punctuation

22. Proofread you writing.

As a former English teacher I really got a kick out of reading this column. Even though I did not write it, I just had to share. Hope you enjoyed. I’ll keep on the lookout for future words of wisdom from him that I can share at a later date.

When the Student is Ready, the Teacher will Appear

Marylyn E. Calabrese

writedrmec@aol.com

There I was on the New Jersey turnpike, driving to meet a business client who needed help in improving his writing. I was so nervous I was sick to my stomach. Why had I agreed to do this?

Several months earlier, I had met the mother of one of my high school students at a poetry fest. She was a management consultant and looking for someone who could provide writing coaching to several of her clients. Was I interested? Maybe, but…

At that time, I was a full time high school English teacher, teaching literature and writing and also spending a lot of time correcting my students’ papers. What did I know about the world of high-powered executives and business writing?

After much soul searching, I agreed to give it a try, but only at the end of a regular school day.

Nevertheless, on that long trip up the turnpike, I began to have second thoughts. The man I was going to meet was a young oil executive, a field about which I knew nothing. How was I going to even understand his documents?

Was this new venture of mine totally crazy?

I needed a sign.

The week before my meeting, I prepared. Over the phone I spoke with the man’s supervisor who explained that the client, Harry (not his real name), had recently been promoted to head the computer division of the communications department. Holding this position, he had to instruct, coordinate, and set up all procedures and operations. Basically, his job depended on being able to communicate clearly to his staff.

According to the boss, Harry’s writing was unclear, overwritten, and lacking in basic organization.

Before I drove to meet him, I reviewed the writing samples that had been sent to me in advance, and I checked in with Harry’s staff. Everyone agreed: Harry’s writing was very hard to understand.

When I finally reached the company where he worked, I found his office and knocked on the door.

Harry appeared.

I was stunned. I knew this man.

Although he was now a tall, handsome, young executive, I remembered him as a teenage track star.

Twenty years before, Harry had been a student in one of my very own English classes!

Although very bright, he had never really applied himself, instead looking out the window of my classroom to the track outside.

“I think we know each other,” I said, going in. He cringed visibly, put his head down on his desk and moaned, “Were you my high school English teacher?”

I managed a “yes” but didn't add what I was really thinking. “Now you’re mine! No more looking out the window!”

At first, we were both a little shy. I congratulated him on his new position, and he mumbled something about getting started.

We made appointments to meet. Harry turned out to be highly motivated and indefatigable in improving his writing.

Sitting side by side at his computer, we reviewed his current and past documents, dealing with unclear opening paragraphs, missing transitions, lack of specifics, weak organization—all the typical problems of an inexperienced writer.

Although this was a dream assignment for me, I found that I had to change some of my usual responding techniques. In fact, in one of our first meetings, Harry asked me if I was going to put red marks on his documents. Ouch!

When Harry was one of my students, correcting and grading his papers was routine. Now that I was working with him as a business client, of course, I did neither.

No longer judging, editing, and correcting, instead, I used reading and questioning as my primary responses. With a hierarchy of concerns, I put meaning and structure first in importance and mechanical errors last.

I called this a coaching model of responding, and I became so comfortable with it that I used it with my students back in my high school classes.

In fact, I even stopped correcting their papers and asked students to find and edit their own errors.

After several months of one-on-one conferences, Harry’s writing improved greatly. It turned out that our meetings were very important in his professional development.

My experience with Harry was very important in my professional life as well. After working with him, I decided to take on other business clients. After several years of coaching business clients after school and teaching high school students, I retired early and became a writing coach.

Yes, when the student was ready, the teacher did appear. And, in my case, when the teacher was ready, she learned a lot from her student.

writedrmec@aol.com

There I was on the New Jersey turnpike, driving to meet a business client who needed help in improving his writing. I was so nervous I was sick to my stomach. Why had I agreed to do this?

Several months earlier, I had met the mother of one of my high school students at a poetry fest. She was a management consultant and looking for someone who could provide writing coaching to several of her clients. Was I interested? Maybe, but…

At that time, I was a full time high school English teacher, teaching literature and writing and also spending a lot of time correcting my students’ papers. What did I know about the world of high-powered executives and business writing?

After much soul searching, I agreed to give it a try, but only at the end of a regular school day.

Nevertheless, on that long trip up the turnpike, I began to have second thoughts. The man I was going to meet was a young oil executive, a field about which I knew nothing. How was I going to even understand his documents?

Was this new venture of mine totally crazy?

I needed a sign.

The week before my meeting, I prepared. Over the phone I spoke with the man’s supervisor who explained that the client, Harry (not his real name), had recently been promoted to head the computer division of the communications department. Holding this position, he had to instruct, coordinate, and set up all procedures and operations. Basically, his job depended on being able to communicate clearly to his staff.

According to the boss, Harry’s writing was unclear, overwritten, and lacking in basic organization.

Before I drove to meet him, I reviewed the writing samples that had been sent to me in advance, and I checked in with Harry’s staff. Everyone agreed: Harry’s writing was very hard to understand.

When I finally reached the company where he worked, I found his office and knocked on the door.

Harry appeared.

I was stunned. I knew this man.

Although he was now a tall, handsome, young executive, I remembered him as a teenage track star.

Twenty years before, Harry had been a student in one of my very own English classes!

Although very bright, he had never really applied himself, instead looking out the window of my classroom to the track outside.

“I think we know each other,” I said, going in. He cringed visibly, put his head down on his desk and moaned, “Were you my high school English teacher?”

I managed a “yes” but didn't add what I was really thinking. “Now you’re mine! No more looking out the window!”

At first, we were both a little shy. I congratulated him on his new position, and he mumbled something about getting started.

We made appointments to meet. Harry turned out to be highly motivated and indefatigable in improving his writing.

Sitting side by side at his computer, we reviewed his current and past documents, dealing with unclear opening paragraphs, missing transitions, lack of specifics, weak organization—all the typical problems of an inexperienced writer.

Although this was a dream assignment for me, I found that I had to change some of my usual responding techniques. In fact, in one of our first meetings, Harry asked me if I was going to put red marks on his documents. Ouch!

When Harry was one of my students, correcting and grading his papers was routine. Now that I was working with him as a business client, of course, I did neither.

No longer judging, editing, and correcting, instead, I used reading and questioning as my primary responses. With a hierarchy of concerns, I put meaning and structure first in importance and mechanical errors last.

I called this a coaching model of responding, and I became so comfortable with it that I used it with my students back in my high school classes.

In fact, I even stopped correcting their papers and asked students to find and edit their own errors.

After several months of one-on-one conferences, Harry’s writing improved greatly. It turned out that our meetings were very important in his professional development.

My experience with Harry was very important in my professional life as well. After working with him, I decided to take on other business clients. After several years of coaching business clients after school and teaching high school students, I retired early and became a writing coach.

Yes, when the student was ready, the teacher did appear. And, in my case, when the teacher was ready, she learned a lot from her student.

Connecting Passion for Content to Pedagogy

Sarah Mangan

Everyone’s first year of teaching is challenging. Especially since most of us became teachers because we were good students, and thought, “I can totally do that, and, you know what? I’m going to do it in such a way that I change my students’ lives the way [insert name of your most influential teacher here] has changed mine.”

Unfortunately, one of the biggest challenges I faced in my first year of teaching was the realization that not all my students were like I was at their age. Even worse, due to the constant standardized tests in reading and writing, they actually hated my class before it even began. I struggled to balance my inexperience with my desire to do well in the classroom, and to make a connection between the content I needed to teach and my students’ interests. Through trial and error, I picked up some quick fixes for student engagement, but I still had a long way to go, and with an under-served population, I didn't have any time to waste. How could I share my love of English with my students in such a way that they could learn to love it too? And how could I do this while also preparing them for their state tests?

I turned to Paulo Freire for help. In his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he writes, “Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity or it becomes the practice of freedom, the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world” (Freire, 1978). I thought about the type of education Freire proposed: creative, interactive, and transformative. Those were the lessons I remembered from school, when I wrote and created, bringing my own wealth of knowledge to the traditional canon of topics.

I remember writing a prologue in iambic pentameter for my own version of The Canterbury Tales in which my travelers were going to space. I remember writing a scene from a play in an absurdist style after reading Waiting for Godot. I remember creating scenarios for physics problems, and presenting them for my classmates to solve. Most of all, I remember my teachers, and their enthusiasm as they presented their assignments to us.

It was then that I realized what I had to do in order to connect with my new students and engage them in learning. To be an effective teacher, I had to first be passionate about my content area, and then embed creative tasks within my curriculum. I decided to do this for two reasons: (1) I truly missed writing, and without any hobbies, I began to depend on my irregular success in the classroom for my happiness; and (2) if I provided my students enough outlets through which they could showcase their personal knowledge within the tested curriculum, I knew they would be more likely to make connections to the content.

When I finally had my plan together, the Keystone tests were only weeks away, so I continued preparing my students for the test, while beginning the transformation of my classroom with myself. At my university, aspiring educators majored in what they wanted to teach for their Undergraduate degree, and focused on education during their Graduate program studies. Because of this, I earned my Bachelors in Creative Writing, something that had been an on-again-off-again hobby since I was three years old. I had been playing with a book idea for years, a series of young-adult science fiction adventure books inspired by my love of The Hunger Games and Divergent. Though I had no idea where I wanted them to go, I began to write. Slowly, at first, as my creative muscles adjusted, but by the first weekend in April, I had my first chapter.

I wrote furiously. By the time my students were taking the Keystones, I had 200 pages written, and a plan for the rest of my first book. I realized something: I was not just a teacher, and my worth could not be reduced to a proficiency grade on a state test. I was also a writer, and I was owning that.

Subconsciously, I must have begun teaching more passionately, because while I was focusing my efforts on my own transformation, my students were changing too. On the Literature Keystone test days, a few students boasted, “I’m going to pass this.” I wondered why they were so invested in the test when I realized: Through the process of writing, I had become so positive and excited about literature that they had picked up on it too. My change in attitude made all the difference, and after they took the Literature Keystone test, they thanked me for preparing them. I was voted “Best Teacher” for the yearbook, and I left for summer vacation with hugs, words of encouragement, and the determination to transform my classroom into a space of creative learning, specifically through writing.

That summer I created a curriculum for the following year, one that I would teach through writing. Through this process, we would examine and analyze author’s choices in fiction and nonfiction pieces, specifically concerning theme, voice, bias, mood, setting, character, and plot. After reading our sample texts (from articles to poems to novels), we would apply what we had learned from reading and studying the texts to our own writing in order to strengthen our skills. We would write frequently in a notebook, and I would check student work for grammatical and spelling errors to help improve written writing skills. At the end of the year, students would produce a short piece of fiction that is all their own and that they can take pride in, thereby strengthening their confidence in English as well as their ownership over their learning. As summer ended, I tweaked my curriculum, and finished writing my first novel.

On the first day of school, I passed out the syllabus, and groans rippled through the room. “You can do it. The first step is trying,” I reminded them over and over again, but they didn't buy into it. That is, until our first creative writing assignment.

We were about to read “A Good Man is Hard to Find” by Flannery O’Connor, and I wanted to provide prior knowledge to my students. Before we even began our creative writing task, we read the first paragraph of the story using close reading methods. First students read it and marked it on their own. Then, they synthesized their findings with a neighbor, and each partnered group reported out their shared analysis to the whole class, after which point we began a full class discussion. We analyzed how the characters interacted and spoke to each other, we used our analysis to draw conclusions about who they were as characters, and we made conjectures about what exactly The Misfit had done and how he had escaped.

After this I asked my students to open their notebooks for class, and number the lines in columns from 1 to 100. I told students that they were going to write only 100 words from the perspective of The Misfit. I told them they had just escaped, and that they had hopped a train, since The Misfit was last seen en route to Florida. They could decide where on the train they were, what they were wearing, how they felt about the people on the train if they interacted, what they had done to land in jail, whether or not they still identified as a criminal, and why they were called “The Misfit.” Many of my students have family members, friends, or neighbors who have been or are currently in prison, so I was sure to give them the option to allow The Misfit to be wrongfully accused or reformed. Through considering all of these questions as they wrote, students were critically thinking and problem solving, not to mention analyzing how the first paragraph’s language influences readers’ perceptions of characters.

I told students to take it just one word at a time, but since each word had its own space, to choose their wording and vocabulary carefully. For example, if they wanted The Misfit to “sit with a thud” on the seat, to instead use a stronger verb, like “plop.” In this way, we were practicing our vocabulary and basic writing skills.

I wrote a few sentence starters of varying lengths on the board to differentiate for students who needed more help getting started. I set a timer for 10 minutes, though based on their progress, I gave them more time if needed.

When my students began writing, I played train sounds through my computer, and encouraged them to incorporate more than one sensory detail in their descriptions. By using the sounds, they also considered mood, a concept often difficult for students to grasp. How did the sounds make them feel? How did The Misfit respond or not respond to these sounds?

I walked around to monitor progress, before I realized: I’m a writer, too! I am doing this, because I am passionate about writing and believe in its value. My passion was what had sold them the year before, wasn't it? I had to continue sharing my passion if I wanted to repeat that success. I sat down in an empty seat, and wrote my own 100 word piece.

When the timer ran out, I allowed them a minute or two to look over their work and change anything they might want to before sharing. I asked for volunteers to read their work, fully expecting to be the only one, but hands shot up. I was shocked. Volunteers took turns reading their work, and it was amazing how many variations were presented. There were pieces in which The Misfit was innocent and trying desperately not to see the fear on the other passengers faces; there were pieces in which the police found him, and he had to escape the train for freedom; there were pieces in which he looked around the train car plotting who his next victim would be; and there was even a fantasy piece in which The Misfit earned his name from his purple eyes, which also gave him supernatural powers, thereby making him a misfit. It was amazing, and I wasn't the only one who thought so. At the end of the semester, when I asked students to gather their best 5 pieces in their notebooks for me to grade, nearly all of them included their Misfit story. It was a source of pride for many of them, because it was the first time they had created something like that using only their imagination and evidence from the text.

When we began reading “A Good Man is Hard to Find” the next day, they were so engaged. Not one student interrupted the reading or even went to the bathroom. They were glued to the story, because they genuinely wanted to know who The Misfit was, what he had done, and if he was anything like the character they’d written the day before. When we finished reading, my students were emotionally invested in what happened, and the analytical responses they turned in were their strongest pieces of writing yet.

The year continued this way, and as they continued writing, I shared my writing, my successes, and my failures with them too. I was most amazed when, after sharing my query letter for Book 1, my students gave me valuable and applicable feedback. They felt comfortable and confident enough in their literacy to tell me when a sentence felt too cluttered or choppy. They even felt comfortable enough to tell me when something didn't sound very exciting, and gave me valuable suggestions for revision. Just as I was now taking ownership over my writing and my voice, so were my students.

Finally, it was time to take the Keystone tests, and to my surprise, all of my students were confident about their success. Each and every one of my students truly believed that they would do well, even those who struggled. Still, I wanted to remind them that no matter what the test said, I knew that they had grown, and their writing had shown definitively that they had grown. “Could you have written a story like this at the start of this year?” I asked them. They shook their heads. “You are all writers now. No one can take that from you.”

Not surprisingly, as soon as I began incorporating creativity into my class and began fostering my students’ ownership over their work, their involvement and behavior in class drastically improved. All year my students had been engaging in such thorough critical thinking that by the time they took the Keystone Literature test, it was just another task.

From this experience, I truly believe that a teacher must be passionate about their subject in order to be successful. If not, why should their students love it or take any ownership over their own work? If we want to make learning engaging, we must channel our passions into transforming ourselves into experts of our content with an appreciation for our students’ unique voices. Only then can we begin to bridge the gaps between student achievement levels, and between our content and our students.

Works Cited

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Harmondsworth, Middlesex ˜œ: Penguin, 1978. Print.

Everyone’s first year of teaching is challenging. Especially since most of us became teachers because we were good students, and thought, “I can totally do that, and, you know what? I’m going to do it in such a way that I change my students’ lives the way [insert name of your most influential teacher here] has changed mine.”

Unfortunately, one of the biggest challenges I faced in my first year of teaching was the realization that not all my students were like I was at their age. Even worse, due to the constant standardized tests in reading and writing, they actually hated my class before it even began. I struggled to balance my inexperience with my desire to do well in the classroom, and to make a connection between the content I needed to teach and my students’ interests. Through trial and error, I picked up some quick fixes for student engagement, but I still had a long way to go, and with an under-served population, I didn't have any time to waste. How could I share my love of English with my students in such a way that they could learn to love it too? And how could I do this while also preparing them for their state tests?

I turned to Paulo Freire for help. In his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he writes, “Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity or it becomes the practice of freedom, the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world” (Freire, 1978). I thought about the type of education Freire proposed: creative, interactive, and transformative. Those were the lessons I remembered from school, when I wrote and created, bringing my own wealth of knowledge to the traditional canon of topics.

I remember writing a prologue in iambic pentameter for my own version of The Canterbury Tales in which my travelers were going to space. I remember writing a scene from a play in an absurdist style after reading Waiting for Godot. I remember creating scenarios for physics problems, and presenting them for my classmates to solve. Most of all, I remember my teachers, and their enthusiasm as they presented their assignments to us.

It was then that I realized what I had to do in order to connect with my new students and engage them in learning. To be an effective teacher, I had to first be passionate about my content area, and then embed creative tasks within my curriculum. I decided to do this for two reasons: (1) I truly missed writing, and without any hobbies, I began to depend on my irregular success in the classroom for my happiness; and (2) if I provided my students enough outlets through which they could showcase their personal knowledge within the tested curriculum, I knew they would be more likely to make connections to the content.

When I finally had my plan together, the Keystone tests were only weeks away, so I continued preparing my students for the test, while beginning the transformation of my classroom with myself. At my university, aspiring educators majored in what they wanted to teach for their Undergraduate degree, and focused on education during their Graduate program studies. Because of this, I earned my Bachelors in Creative Writing, something that had been an on-again-off-again hobby since I was three years old. I had been playing with a book idea for years, a series of young-adult science fiction adventure books inspired by my love of The Hunger Games and Divergent. Though I had no idea where I wanted them to go, I began to write. Slowly, at first, as my creative muscles adjusted, but by the first weekend in April, I had my first chapter.

I wrote furiously. By the time my students were taking the Keystones, I had 200 pages written, and a plan for the rest of my first book. I realized something: I was not just a teacher, and my worth could not be reduced to a proficiency grade on a state test. I was also a writer, and I was owning that.

Subconsciously, I must have begun teaching more passionately, because while I was focusing my efforts on my own transformation, my students were changing too. On the Literature Keystone test days, a few students boasted, “I’m going to pass this.” I wondered why they were so invested in the test when I realized: Through the process of writing, I had become so positive and excited about literature that they had picked up on it too. My change in attitude made all the difference, and after they took the Literature Keystone test, they thanked me for preparing them. I was voted “Best Teacher” for the yearbook, and I left for summer vacation with hugs, words of encouragement, and the determination to transform my classroom into a space of creative learning, specifically through writing.

That summer I created a curriculum for the following year, one that I would teach through writing. Through this process, we would examine and analyze author’s choices in fiction and nonfiction pieces, specifically concerning theme, voice, bias, mood, setting, character, and plot. After reading our sample texts (from articles to poems to novels), we would apply what we had learned from reading and studying the texts to our own writing in order to strengthen our skills. We would write frequently in a notebook, and I would check student work for grammatical and spelling errors to help improve written writing skills. At the end of the year, students would produce a short piece of fiction that is all their own and that they can take pride in, thereby strengthening their confidence in English as well as their ownership over their learning. As summer ended, I tweaked my curriculum, and finished writing my first novel.

On the first day of school, I passed out the syllabus, and groans rippled through the room. “You can do it. The first step is trying,” I reminded them over and over again, but they didn't buy into it. That is, until our first creative writing assignment.

We were about to read “A Good Man is Hard to Find” by Flannery O’Connor, and I wanted to provide prior knowledge to my students. Before we even began our creative writing task, we read the first paragraph of the story using close reading methods. First students read it and marked it on their own. Then, they synthesized their findings with a neighbor, and each partnered group reported out their shared analysis to the whole class, after which point we began a full class discussion. We analyzed how the characters interacted and spoke to each other, we used our analysis to draw conclusions about who they were as characters, and we made conjectures about what exactly The Misfit had done and how he had escaped.

After this I asked my students to open their notebooks for class, and number the lines in columns from 1 to 100. I told students that they were going to write only 100 words from the perspective of The Misfit. I told them they had just escaped, and that they had hopped a train, since The Misfit was last seen en route to Florida. They could decide where on the train they were, what they were wearing, how they felt about the people on the train if they interacted, what they had done to land in jail, whether or not they still identified as a criminal, and why they were called “The Misfit.” Many of my students have family members, friends, or neighbors who have been or are currently in prison, so I was sure to give them the option to allow The Misfit to be wrongfully accused or reformed. Through considering all of these questions as they wrote, students were critically thinking and problem solving, not to mention analyzing how the first paragraph’s language influences readers’ perceptions of characters.

I told students to take it just one word at a time, but since each word had its own space, to choose their wording and vocabulary carefully. For example, if they wanted The Misfit to “sit with a thud” on the seat, to instead use a stronger verb, like “plop.” In this way, we were practicing our vocabulary and basic writing skills.

I wrote a few sentence starters of varying lengths on the board to differentiate for students who needed more help getting started. I set a timer for 10 minutes, though based on their progress, I gave them more time if needed.

When my students began writing, I played train sounds through my computer, and encouraged them to incorporate more than one sensory detail in their descriptions. By using the sounds, they also considered mood, a concept often difficult for students to grasp. How did the sounds make them feel? How did The Misfit respond or not respond to these sounds?

I walked around to monitor progress, before I realized: I’m a writer, too! I am doing this, because I am passionate about writing and believe in its value. My passion was what had sold them the year before, wasn't it? I had to continue sharing my passion if I wanted to repeat that success. I sat down in an empty seat, and wrote my own 100 word piece.

When the timer ran out, I allowed them a minute or two to look over their work and change anything they might want to before sharing. I asked for volunteers to read their work, fully expecting to be the only one, but hands shot up. I was shocked. Volunteers took turns reading their work, and it was amazing how many variations were presented. There were pieces in which The Misfit was innocent and trying desperately not to see the fear on the other passengers faces; there were pieces in which the police found him, and he had to escape the train for freedom; there were pieces in which he looked around the train car plotting who his next victim would be; and there was even a fantasy piece in which The Misfit earned his name from his purple eyes, which also gave him supernatural powers, thereby making him a misfit. It was amazing, and I wasn't the only one who thought so. At the end of the semester, when I asked students to gather their best 5 pieces in their notebooks for me to grade, nearly all of them included their Misfit story. It was a source of pride for many of them, because it was the first time they had created something like that using only their imagination and evidence from the text.

When we began reading “A Good Man is Hard to Find” the next day, they were so engaged. Not one student interrupted the reading or even went to the bathroom. They were glued to the story, because they genuinely wanted to know who The Misfit was, what he had done, and if he was anything like the character they’d written the day before. When we finished reading, my students were emotionally invested in what happened, and the analytical responses they turned in were their strongest pieces of writing yet.

The year continued this way, and as they continued writing, I shared my writing, my successes, and my failures with them too. I was most amazed when, after sharing my query letter for Book 1, my students gave me valuable and applicable feedback. They felt comfortable and confident enough in their literacy to tell me when a sentence felt too cluttered or choppy. They even felt comfortable enough to tell me when something didn't sound very exciting, and gave me valuable suggestions for revision. Just as I was now taking ownership over my writing and my voice, so were my students.

Finally, it was time to take the Keystone tests, and to my surprise, all of my students were confident about their success. Each and every one of my students truly believed that they would do well, even those who struggled. Still, I wanted to remind them that no matter what the test said, I knew that they had grown, and their writing had shown definitively that they had grown. “Could you have written a story like this at the start of this year?” I asked them. They shook their heads. “You are all writers now. No one can take that from you.”

Not surprisingly, as soon as I began incorporating creativity into my class and began fostering my students’ ownership over their work, their involvement and behavior in class drastically improved. All year my students had been engaging in such thorough critical thinking that by the time they took the Keystone Literature test, it was just another task.

From this experience, I truly believe that a teacher must be passionate about their subject in order to be successful. If not, why should their students love it or take any ownership over their own work? If we want to make learning engaging, we must channel our passions into transforming ourselves into experts of our content with an appreciation for our students’ unique voices. Only then can we begin to bridge the gaps between student achievement levels, and between our content and our students.

Works Cited

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Harmondsworth, Middlesex ˜œ: Penguin, 1978. Print.

Co-Teaching: Fostering a Professional Relationship

Natalie Green

Introduction

By nature, teachers are territorial. The classroom is the sacred ground from which we mold young minds, spark passion for learning, and inspire the future. The classroom is also where we eat breakfast (or skip it), deal with crises big and small, miraculously stretch supplies, and it is where our personal lives cease to exist for the next eight hours (or more.) We own that space. It is our home turf, our corner office, our driver’s seat.

We like being the mastermind of the learning experience. We carefully plan our lessons, and employ our well-honed style of leadership. We’re willing to adapt if something unexpected comes up, but our well-laid plan leaves little chance for unpleasant surprises.

What happens to our autonomy, then, when we are paired with another adult to co-teach? Can we maintain our identity as teachers, as well as share control with a colleague?

Co-teaching, as its name suggests, requires that two teachers share the responsibilities of planning, instruction, record-keeping, classroom management and communicating with parents. The old adage, “two heads are better than one”, is the foundation of co-teaching. Both teachers bring their expertise and talents to the classroom, and together they create a richer learning experience for students than could be accomplished alone.

Just like any other relationship, the partnership between co-teachers needs attention, understanding, and respect. Relationships build over time, but co-teachers are expected to share space, authority and control immediately after being assigned to work together. Thus, the fine points of the relationship between co-teachers are worked out as instruction occurs, which isn't necessarily ideal for students.

Even seasoned co-teaching partners need to work on their relationship as colleagues. Every school year brings on new challenges, and co-teachers need to refocus their relationship when reunited after that long summer break.

My story

I am a secondary English teacher, and in my district, many of the general core courses are inclusion classes. The expectation from the district is that the content teacher and the learning support teacher negotiate their own relationship in the classroom in a manner that best supports all students’ needs. In a given school year, I typically work with two different co-teachers for the courses I am assigned to teach.

In the past nine years, I have taught with five different inclusion partners (plus three maternity leave substitutes), in three different courses. Each of these co-teaching relationships has been different from one another, primarily because of the personalities being blended and the expectations we each had about the co-teaching situation. Needless to say, some relationships have been better than others.

On the whole, however, I have had wonderful experiences with co-teaching and find that with a compatible match, co-teaching can create phenomenal learning experiences for students as well as rewarding instructional experiences for the teachers.

Three attributes that help develop a positive relationship between colleagues have emerged throughout my experiences as a co-teacher.

1. Cohabitation

Comfortably sharing space is the ultimate test of trust and compatibility between two people. Like newly-weds merging their possessions from their single lives, co-teachers need to negotiate how their separate habits and routines will come together in the classroom. Students are acutely aware of the relationship between co-teachers, and will pick up on any friction that exists. Like those newly-weds figuring out who will do the grocery shopping, cut the grass and take out the garbage, co-teachers need to work out a routine together in their shared space. This action can set the tone for their relationship.

In some instances, co-teachers truly share the physical space of a classroom; both teachers have a desk and they work together to arrange the space to best accommodate students and the type of learning activities that have been planned. However, most co-teaching scenarios involve one teacher coming into, or visiting, the classroom space designated for the other teacher.